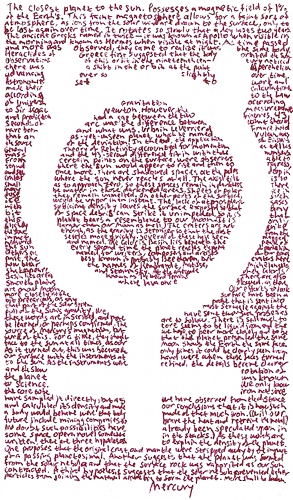

By the time I’d gotten to Neptune, it was the fourth of the planetary Word Art pieces I had done on that particular Thursday and I was enormously relieved that Pluto was no longer on the list. I was worried I wouldn’t find much to write about since its far distance meant that, like Uranus, there were no ancient myths surrounding it and not much in the way of exploration, either. Fortunately, there was one thing that fascinated me–the astronomical race to be the first to officially discover the planet once the possibility of its existence came to light.

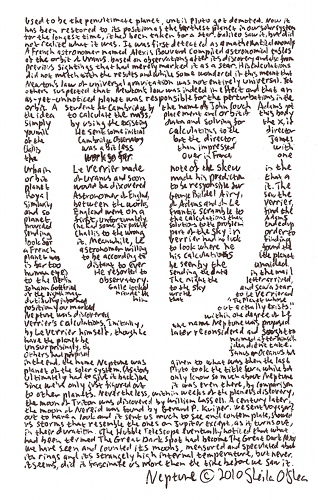

Used to be the penultimate planet, until Pluto got demoted.

Now it has been restored to its position as the farthest planet in our solar system.

For the longest time, it had been taken as a star.

Galileo saw it, but did not realize what it was.

It was first detected as a mathematical anomaly.

A French astronomer named Alexis Bouvard compiled astronomical tables of the orbit of Uranus, based on observations after its discovery and also from previous sightings that had merely marked it as a star.

His calculations did not match with the results and while some wondered if this meant that Newton’s law of universal gravitation was not entirely universal.

Yet others suspected that Newton’s law was indeed still in effect and that an as-yet-unnoticed planet was responsible for the perturbations in the orbit.

A student at Cambridge by the name of John Couch Adams got the idea to calculate the mass, placement and orbit of this body simply by using the existing data and solving for the x, if you will.

He sent some initial calculations to the director of the Cambridge Observatory but the director, James Challis, was a bit less than impressed with the work so far.

Over in France, one Urbain Le Verrier made note of the skew in the orbit of Uranus and soon made his prediction that a planet would be discovered to be responsible for it.

The Royal Astronomer of England, George Biddel Airy, saw the similarity between the works of Adams and of Le Verrier, and so England went on a frantic scramble to find the planet first.

Unfortunately, the calculations that Adams provided (he had some six possible solutions to the problem) ended up sending Challis to the wrong part of the sky in order to look for it.

Meanwhile, Le Verrier had no luck finding a French astronomer willing to look where he found the planet was to be according to his calculations (the planet is far too distant to ever be seen by the unaided human eye.)

He resorted to sending the data in the mail to the Berlin Observatory.

The night the letter arrived, Johann Gottfried Galle looked to the sky and saw a star of the eighth magnitude.

He wrote to Le Verrier and dutifully informed him that “The planet whose position you marked out actually exists.”

Neptune was discovered within one degree of Le Verrier’s calculations.

Initially, the name Neptune was proposed by Le Verrier himself, though he later reconsidered and sought to have the planet be named after himself.

Unsurprisingly, the idea didn’t take.

Others had proposed Janus or Oceanus, but in the end, the name Neptune was given to what was then the last planet of the solar system.

(As above, Pluto took the title for a while but ultimately had to give it back.)

We only know so much about Neptune since we’ve only just figured out it was even there, by comparison to other planets.

Nevertheless, within weeks of the planet’s discovery, the moon of Triton was discovered by William Lassell.

A century later, the moon of Nereid was found by Gerard P. Kuiper.

We sent Voyager 2 out to have a look and it sent us much to see and contemplate, showed us storms that resemble the ones on Jupiter except, as it turns out, in their duration.

(The Hubble Telescope eventually noticed that what had been termed The Great Dark Spot eventually had become the Great Dark Not.)

We have seen and counted its moons, measured and speculated about its rings and its strangely high internal temperature, but never, it seems, did it fascinate us more than the time before we saw it.

I finished a little before ten o’clock that night and was left both restless and exhausted. Friday morning was spent doing last minute scanning and framing and packing all the planets up to take to Chattanooga with me. None of them sold at the time, but I received many compliments on my work and it gave me some glimmer of hope that this crazy scribbly thing I do may will be of interest to others.

Prints of this work are available here.

The original is not for sale.